Here are some of the books I’ve read (and a few movies, too). Feel free to quibble with the opinions, but please keep it clean.

- Micro-Review #165: The False Prophetby stevenowad

by Claire Booth Taylor Helzer was raised a devout Mormon, a wunderkind of the faith, fast-tracked for a life on the pulpit. So how does he go from religious prodigy to stockbroker and New Age dabbler and then to conman and mass murderer?

Claire Booth’s treatment of Helzer’s story is clear-eyed and detailed. It doesn’t pigeonhole Helzer or sensationalize his life and deeds (even if the book’s cover does). It tracks Helzer’s growth with what looks like journalistic fairness. Without seeking to indict the Mormon church, it also indicts it (or we do, once we absorb the facts). It lacks the range of Jon Krakauer’s Under the Banner of Heaven and the urgency of Netflix’s Evil Influencer, but a common thread runs through all three works. Too much religion in an insular community can be a dangerous thing. This is one of the good true crime books on the market.

- Micro-Review #164: No Ordinary Assignmentby stevenowad

by Jane Ferguson In an era full of war-reporter memoirs, this is one of the better ones. It comes across as honest and objective, which is an accomplishment given the emotional nature of the author’s job.

Born and raised during “the Troubles” in Northern Ireland, Ferguson learns about war before most of us do. As a young journalist scrounging to break into the business despite the drawback of being a female with only average looks, she knows the odds of getting paid to cover wars for television are long. But she perseveres, along the way falling in love with pre-war Yemen and never losing sight of the goal, which is to cover not wars, but the people in them.

Ferguson’s personal journey aside, this book serves as a refresher on recent Middle East history, from a still-functioning Lebanon to the glorious hopes of the Arab Spring and the crushing weight of entrenched autocratic tendencies. All of this is synthesized and served in a way that won’t alienate history-challenged readers. I give it the proverbial two thumbs up.

- Micro-Review #163: Swimming to Cambodiaby stevenowad

by Spalding Gray This slim volume is a transcription of Gray’s stage monologues about his time on the set of THE KILLING FIELDS in Thailand in the early 1980s.

As an almost aggressively introspective New York stage actor scrambling for film jobs, Gray is out of place in the world of film—especially when the movie is about genocide and is being shot in a third world country. Still, he goes to Thailand in search of “the perfect moment,” a flash of ultimate poetic understanding.

Does this type of literary self-indulgence hold up well in 2025? Very much so. The psychoanalytical ruminations are scented with ’80s therapy-speak, but they’re also infused with a humor that’s both amusingly self-deprecating and undeniably intelligent. The book is a breezy, stimulating read, complete with Hollywood gossip and a surprisingly fascinating character arc. It won’t give you your own perfect moment, but it’ll put you in a good frame of mind.

- Micro-Review #162: Macbeth (2015)by stevenowad

directed by Justin Kurzel Of the more than 90 screen versions of Shakespeare’s second-most-famous tragedy, this one, from 2015 and featuring Michael Fassbender and Marion Cotillard, is among the most cinematic. Suffused with first-half scene jumping, stunning visuals and blood-soaked action, this is clearly a movie, not a play. Most of the Bard’s verbiage doesn’t make it onto the screen, but the lines that do are faithful to the original, showing us the Scottish king’s ambition and cruelty as well as guilt, paranoia, madness and roughly 100 other heavy themes.

There’s nothing subtle here. Everything is supercharged and severe, with no time to recalibrate and catch your breath. Watch this with the subtitles on or miss brilliant wordplay and provocative subtext. And enjoy the acting. Despite the lack of tone shifts and a fiercely grim last act, Fassbender et al give powerful performances.

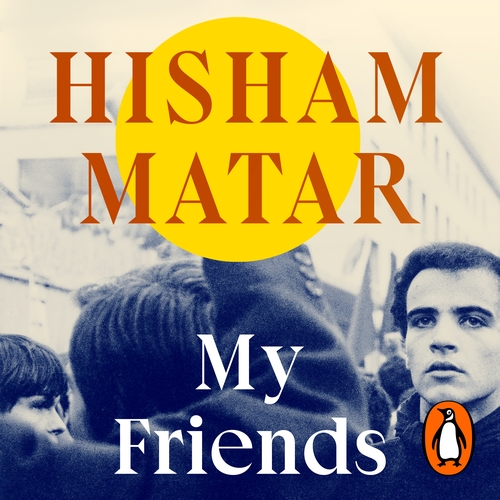

- Micro-Review #161: My Friendsby stevenowad

by Hisham Matar Here’s a heavy novel about exile, friendship and family. As a young Libyan student in England in the 1980s, Khaled has literary dreams. But history has other ideas. After a protest at the Libyan embassy, there’s no going home. Now he has to make his way in a foreign land while hopefully keeping Khaddafi’s regime from punishing the family back in Benghazi.

Khaled’s life is a case of not belonging here and not belonging there, of trying to embrace a new world that carries old-world sorrows and longings personified by the trials of fellow exiles. My Friends is sometimes dour and at all times humorless. It’s also intellectual when a touch of human emotion might be more apt, but it’s also hard to put down. For light escapism, go elsewhere. For a good look at what exile does to a person, I can’t think of a better novel.