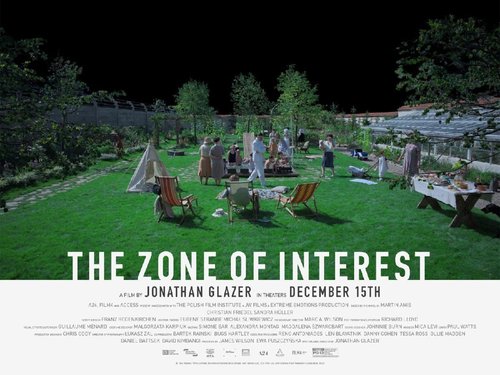

This cinematic portrayal of the first family of Auschwitz is serious and well-intended, but it drowns in its own devotions. The story is direct and largely factual: Commandant Rudolf Hoss works long hours running the camp, while wife Hedwig prunes azaleas and overseas their brood of Aryan offspring. She luxuriates in the midst of horror—and even calls her home “paradise.”

This is Hannah Arendt’s banality of evil, atrocity without emotional engagement. Trains arrive around the clock. Gunshots ring out. Prisoners scream just beyond the wall, but Rudolf and Hedwig rarely acknowledge them. The job is the job, and home is home. For a while, we even question whether Hedwig really knows what’s causing the smoke in that chimney.

Character shading aside, that’s pretty much it: the Hosses as efficient German compartmentalizers, at least until (spoiler alert) the horror grows too heavy and Rudolf suffers a crippling physical reaction. Is there a good artistic reason for suggesting that one of history’s worst schizoid psychopaths suffered wrenching guilt? If so, I can’t see it. The humanizing of Rudolf undercuts the good stuff in this film—and there’s plenty of good. Sandra Huller’s portrayal of Hedwig rings disturbingly true, and the movie’s background sound provides a jarring counterpoint to the stern sterility of the Hoss household. But sometimes evil is just evil, banal or otherwise. The application of poetic license only muddies the historical waters.